Why I Never Contributed To A Roth IRA But Why You Probably Should

2:31 AM My dad is in his 70s and he mentioned he wish he’d started a Roth IRA when he was young. When you’re in your 70s, you must take required minimum distributions from your pre-tax retirement savings accounts and pay taxes.

My dad is in his 70s and he mentioned he wish he’d started a Roth IRA when he was young. When you’re in your 70s, you must take required minimum distributions from your pre-tax retirement savings accounts and pay taxes.

Given nobody likes to pay taxes, I empathized with his regret. But I don’t have a problem paying taxes on income earned. It’s only when I have to pay a surprise tax where the liability wasn’t properly budgeted where I have a problem. This only happened to me once when the state of California passed a retroactive tax of 2.9% for the 2011 tax year.

I’ve been a long time opponent of contributing to the Roth IRA. However, now that I’m older and wiser, let me share some of my excuses and encourage you to contribute to a Roth IRA if you are eligible.

Why I Never Contributed To A Roth IRA

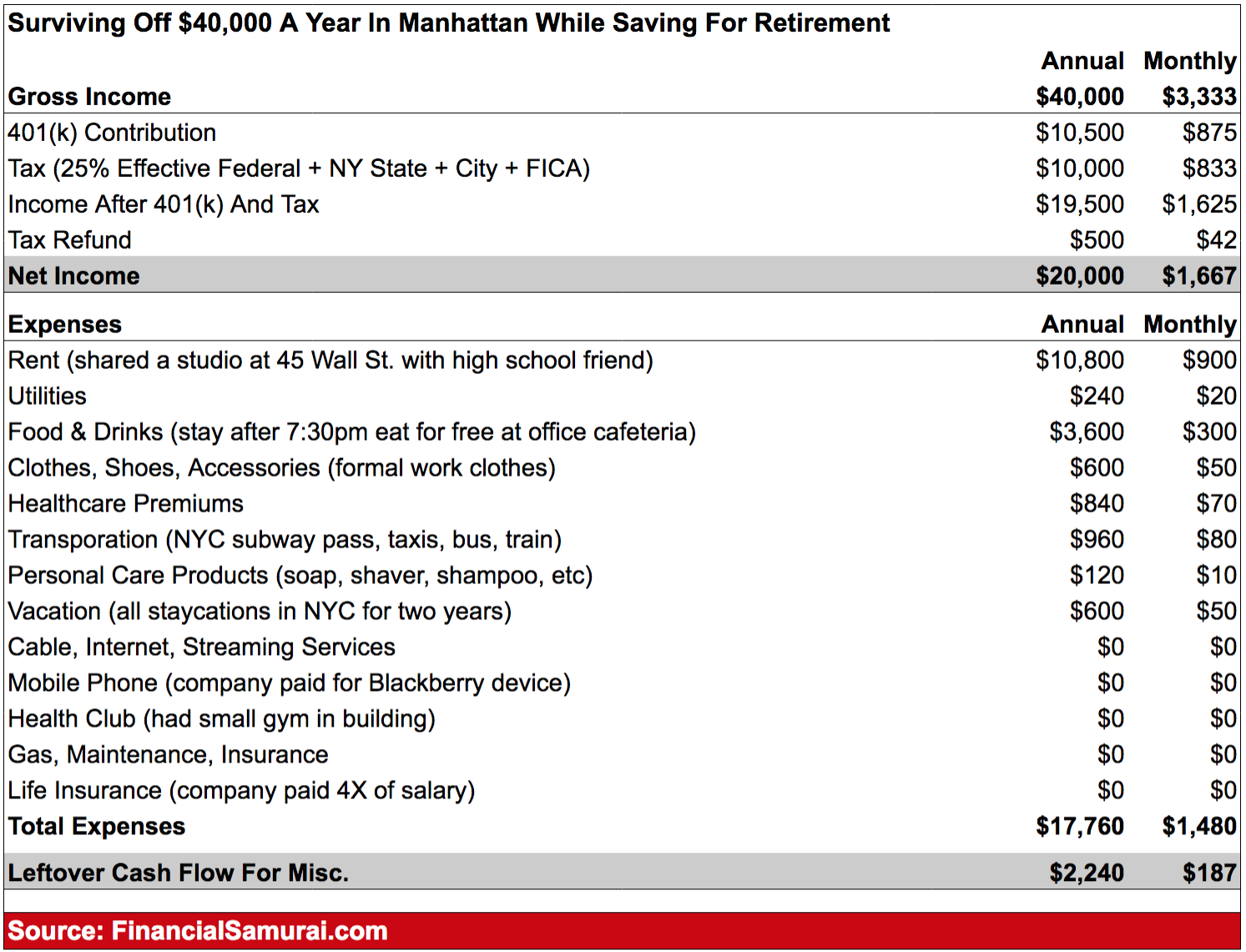

1) I didn’t have much money left over. When I first got a job in 1999, I was only making a $40,000 base salary living in Manhattan. $40,000 did not feel like a lot of money back then, especially since I couldn’t even rent a one bedroom apartment on my own. Even splitting a studio apartment for $1,800 total required my brother-in-law to be a lease co-signer. In NYC, you needed to make at least 40X the monthly rent in annual salary, and my roommate and I did not make over $72,000 combined.

After maxing out my 401(k) to the tune of $10,500 and paying taxes, I didn’t have much left. I needed the ~$200 month left in cash flow to pay for incidentals. Something always tends to come up – like actually having some fun once in a while.

2) I didn’t know any better. The 401(k) was easy to contribute to because it was automatically set up with my employer as part of my employee welcome package. All I had to do was fill out a form indicating how much should be deducted from my paycheck and year-end bonus, if any.

With a Roth IRA, I had to open up a new account, which felt like too much of a PITA at the time, especially given my low cash flow and the amount of hours I was working at the time. When you already not feeling rich, you don’t normally go out of your way to feel poorer. Further, there wasn’t a ubiquity of affordable online brokerage options or personal finance blogs to provide any guidance.

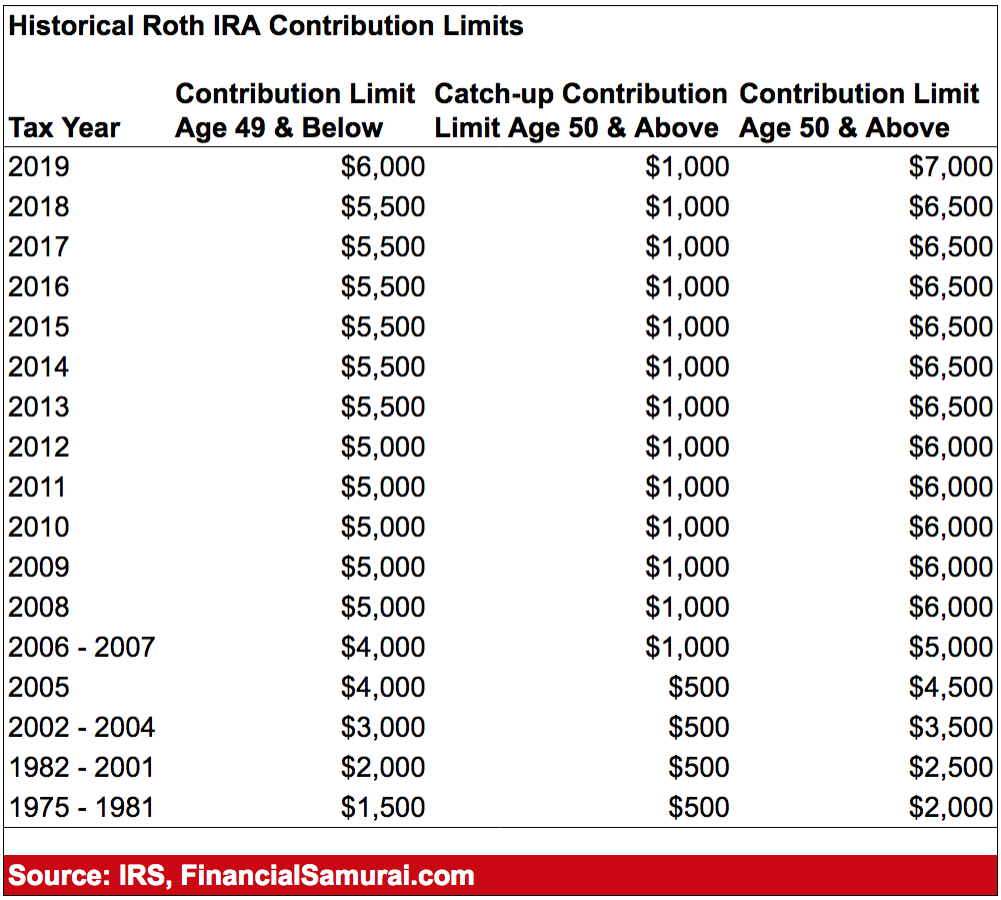

3) The contribution limit was disappointingly low. Even though I only made $40,000 my first year, being able to only contribute $2,000 maximum to a Roth IRA felt underwhelming. At age 22, I would much rather have a $2,000 liquid buffer than lock it up for at least five years. The poorer you are, the more valuable each liquid dollar is.

Check out the historical Roth IRA contribution limits. Only in 2019 has the Roth IRA contribution limit grown to a relatively significant amount of $6,000. The 401(k) max of $19,000 versus the Roth IRA contribution max of $6,000 ratio is now only 3.16X. Back in 1999, the ratio was 5.25X ($10,500 / $2,000), meaning that focusing on the 401(k) was a better choice for me.

4) I hated paying taxes. When you’re struggling to pay for a studio apartment with a friend while also working 70+ hours a week, the last thing you feel like doing is paying more taxes up front, which is what the Roth IRA retirement plan is.

My taxable income was $29,500, which put me at the 28% marginal federal income tax rate at the time ($26,250 – $63,550). Then, of course, I had to pay New York State and City taxes. It felt terrible paying ~30% in taxes for a lousy $2,000 Roth IRA contribution in the hopes that it might get back to $2,000 and then some years later.

The only way I’d feel good paying taxes up front for my Roth IRA contribution is if the effective tax rate was 15% or less and if I was working a leisurely 40 hours a week or less. Working very long hours makes you really bitter about the tax system, especially once you discover a large percentage of working Americans pay zero income taxes.

5) I finally started making too much. When I got my lucky break and moved to San Francisco for a new job, I was making a base salary of $85,000 and was guaranteed a $50,000 bonus. As a result, my total compensation in 2001 was about $120,000, i.e., $10,000 over the maximum $110,000 income allowed for an individual to contribute to a Roth IRA at the time.

Although it was nice to earn more money, it also felt disappointing to be shut out based on an arbitrary income limit. Why wasn’t the income limit $150,000 or $200,000? Was the government saying that not everybody deserves to be treated equally when it comes time to save for their future? It felt that way.

In San Francisco, I still lived extremely frugally, sharing an even cheaper apartment ($1,600/month vs. $1,800/month in NYC) for the first two years. The $40,000 a year lifestyle stayed with me for another four years because I still wasn’t sure I’d be able to survive in the finance world for very long. It was only after I finished my MBA in 2006 and got promoted did I start to spend a little more.

6) I’d be in a lower tax bracket in retirement than while working. This was the main reason why I thought contributing to a Roth IRA was illogical. Not only did I feel federal income tax rates would come down since 1999 (which proved correct), I also believed it would be incredibly hard to amass enough capital to reproduce my average W2 income wage.

For argument’s sake, let’s say I made $100,000 in 1999, meaning that I paid a 31% marginal federal income tax rate, or ~25% effective federal tax rate. My $100,000 turns to $75,000. I would need to accumulate $3,000,000 in capital producing a 2.5% net dividend yield to match my working income tax rate. I was bullish on my future, but not that bullish.

The people who are angry at my after-tax investment targets for early retirement, yet strongly believe in contributing to a Roth IRA are demonstrating inconsistent logic. If you don’t believe you can accumulate multiple millions, then you should not be contributing to a Roth IRA.

Further, I wanted the option to move to one of our no state income tax states in retirement in retirement as well. By contributing to a Roth IRA while working in one of the highest taxed cities in America felt like I was giving up.

Take Advantage Of The Roth IRA When You Can

After reading all my excuses, I hope you’re not more convinced not to contribute to a Roth IRA. Unlike me, be super bullish about your future. I felt so burnt out after a couple years working post college that I thought I was just going to be a beach bum in Hawaii paying zero income taxes for the rest of my life. My grandfather had an old farmhouse I planned on staying in for free, in exchange for maintaining his mango trees.

Today, I’ve warmed up to the Roth IRA because the maximum contribution has increased to a not so insignificant $6,000 a year while the income threshold for contributing has increased as well. The $2,000 maximum contribution between 1982 – 2001 really didn’t feel like much back then, but $6,000 feels like it is meaningful today.

As a single person, you can contribute the maximum if you earn $122,000 or less. Once your modified adjusted gross income is over $137,000, you can no longer contribute. If you are married filing jointly, your MAGI must be less than $203,000, with reductions beginning at $193,000.

$193,000 is a healthy income for married couples that put them in the top 15% of income earners. Even if you live in an expensive area like San Francisco or New York City, at least one partner should be able to max out their 401(k) and contribute the maximum to a Roth IRA.

The Roth IRA is a good idea for tax and retirement diversification purposes. As of now, we are at the bottom end of historical income tax rates and household income generally rises over time. Therefore, if you are eligible to contribute to a Roth IRA, you should.

If I was able to contribute $4,000 on average to a Roth IRA and earn a 9% compound return for 19 years, today I’d have about $200,000 I could withdraw tax-free. Over a 50 year period, my Roth IRA would grow to $3,553,000 with the same terms. That’s not something to sneeze at!

Unfortunately, I’m still not eligible to contribute to a Roth IRA. But if I could I would open one up with an online brokerage account like Fidelity or a digital wealth advisor like Wealthfront and just automatically contribute each month or year. Over a 10+ year period, the amount starts really adding up.

Readers, who is contributing to a Roth IRA and how’s that going? Anybody contribute to a Roth IRA and make more than the income thresholds and have to stop? Is a backdoor or mega backdoor Roth IRA conversion worth it? Anybody now pay more in taxes as a retiree than as a full-time worker?

The post Why I Never Contributed To A Roth IRA But Why You Probably Should appeared first on Financial Samurai.

from Financial Samurai

via Finance Xpress

0 comments